Every week from June through November, I walk a length of beach on Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore (SLBE) that starts at the mouth of the Platte River and runs southwesterly along the shoreline as part of an avian monitoring program.

My transect can be amusingly challenging to get to. The southern access is via a seasonal road that is occasionally passable in my Prius but often has deep potholes. The northern route requires that I cross the Platte River at the mouth. I wade, ford, kayak, and canoe across the river depending upon how deep, wild, and cold it is and who else may be along for the walk. Some years, the mouth has been up to my armpits, but sediment shifts have made it knee-deep in some places the last two years. In October and November, it is safer to kayak across, regardless of depth.

What inspires me to put forth such efforts? I’m looking for birds that are affected by avian botulism. This paralytic disease, caused by the botulinum toxin, commonly results in death for birds (especially waterfowl) and is of growing concern for avian populations in Michigan. There are several different types of botulism. Types C and E can kill waterfowl and fish, and the latter is more prevalent in the Great Lakes.

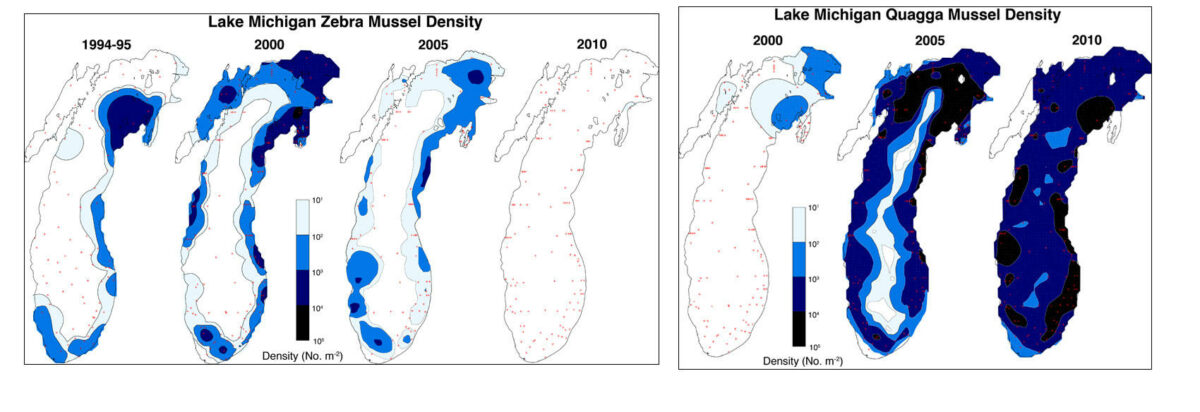

Avian botulism showed up on our shores due to a long sequence of events that started with the introduction of quagga and zebra mussels. Both invasive mussel species have been introduced into the Great Lakes in ballast water in shipping vessels. Zebra mussels were displaced by quagga mussels, which thrive on the muddy lakebed, in the 2000s, and it is said that you could walk across Lake Michigan without leaving a carpet of quagga mussels.

Charts by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Quagga mussels are incredibly effective at cleaning the water of plankton (their food). They filter the water to such an extent that they undermine the entire food chain for native and introduced fish species, such as Chinook salmon. Clearing the water column has resulted in the brilliant blue look of Lake Michigan, a color considered beautiful to the casual observer but also an unfortunate sign for the ecosystem. In 2017, Lake Michigan was declared brighter and clearer than Lake Superior. The downside of crystal-clear Lake Michigan is that more sunlight gets through the water column, and native aquatic vegetation overgrows in the lake bed.

Aquatic plants such as Chara spp. and Cladophora spp. naturally contain the microorganisms that produce botulinum toxin. As the overgrown plants grow and then die in the fall, they wash up on our shores just as fall migrants are moving along Lake Michigan coastlines. Migrating birds feed off the little arthropods in the vegetation, which are themselves accumulating the toxin in their bodies.

Sick birds that are poisoned by botulism exhibit characteristics that can be disheartening to witness. They can’t fly, and when they swim, their necks droop and their wings ineffectively paddle through the water. These birds either drown and wash up or simply die onshore. It is important to bury the birds so they do not infect other scavengers such as gulls, eagles, or coyotes and to prevent flies from laying eggs on the carcasses. Contaminated maggots can also infect our migrating birds.

When I find a dead bird, I record the location using GPS coordinates and bury it. If a bird is “fresh-dead,” I carefully bag it up and deliver it to a freezer at a nearby Sleeping Bear Dunes campground. Recently deceased birds can be necropsied and tested for botulism and other avian maladies. Birds we collect are sent to the USGS National Wildlife Health Center in Madison, Wisc. We are not permitted to collect moribund birds — those showing signs of sickness but yet to be deceased. A call to a supervisor is made when I observe one, so they can look for the bird the next day.

After collecting data for over a decade, here’s what we know: not much. One variable of interest is the number of round gobies found on the beach. The round goby is an invasive fish species that has also been introduced from ballast water. The good news is that round gobies eat quagga mussels (they are the main predator). The bad news is that fish-eating birds, like loons and mergansers, will eat contaminated gobies.

We also see a correlation between bird mortality and temperature. High summer temperatures allow Chara spp. and Cladophora spp. to grow abundantly underwater, creating more habitat for botulinum-toxin-producing bacteria.

Student volunteers help with avian botulism monitoring at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

Many volunteers that monitor for avian botulism have a strong commitment to educating the public about this work. Because we carry a shovel and a backpack, vacationers often wonder if we are digging for clams! I enjoy talking to curious folks about the project — and we have postcard-sized information sheets for those who want to dig deeper — but much of the bird mortality takes place after the summer crowds have disappeared from the lakeshore.

In non-pandemic times, I’m able to bring my ecology students from the Interlochen Arts Academy along on the walk. We stop at the SLBE visitor center in Empire, which has an excellent topographic map of the National Lakeshore (and SLBE swag, of course!). We pick up a hot chocolate at Grocer’s Daughter Chocolate and head for the beach. Teachers ask the students to perform community service as part of our program, and I think it is important to model commitment and consistency to our students.

I have chosen not to include pictures of dead birds with this article because I find them quite disturbing. Fortunately for me, I don’t experience high mortality rates while monitoring my transect, even in the warmest years; I believe wave action pushes dead and drowning birds farther north for my “Bot Squad” colleagues to find.

Most weeks, I find only peace, quiet, and joy on a beautiful beach and have been able to add birds to my life list while volunteering: Red-throated Loon and White-winged Scoter among them. I get to document many living birds — rafts of mergansers, Caspian Terns mixed in with Ring-billed Gulls, and, in most years, Piping Plovers — while I traverse my transect.

This volunteer project can be difficult and some people may find monitoring for dead or sick birds to be too morbid for them, but I encourage everyone to put their passion for birds to work and find a conservation or research effort that they can take part in.

Piping Plover at Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore.

Learn more about avian botulism and how you can help at:

Tip of the Mitt Watershed Council

watershedcouncil.org

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore

nps.gov/slbe

Michigan Sea Grant

michiganseagrant.org

Michigan DNR

michigan.gov/documents/dnr/Botulism_Manual_2012_390795_7.pdf

To report a sick or dead bird, you can fill out the Eyes in the Field observation form by the Michigan DNR or call the Wildlife Disease Laboratory at 517-336-5030.

~ Mary Ellen Newport, Ph.D.

Featured photo: White-winged Scoter with a mouthful of mussels. Photo by Mike Burrell | Flickr

Mary Ellen Newport, Ph.D., is an ecology instructor and the director of R.B. Annis Department of Math & Science at Interlochen Arts Academy. Dr. Newport is an evolutionary biologist with an interest in conservation biology. Her doctoral and postdoctoral work was in the areas of population and quantitative genetics. She is a volunteer for Michigan’s birds, working with the “Bot Squad” of the National Park Service to monitor botulism toxicity in migrating waterfowl. As an experienced educator and scientist on the Squad, Dr. Newport’s valuable volunteer work also lends her the opportunity to educate the public about the long chain of events triggered by the introduction of invasive species and what we can do to help.